The Arab jurist Ibn al-Qass1 was born at the end of the ninth century and died in 946. He had excellent knowledge of Islamic law and was the author of many theological works. Among these is the work Kitab dala’il al-qibla in which is recorded, for the first time, a highly significant description of the rite of the Holy Fire.

This work is preserved in five manuscripts2 and was first published in 1913 by the Arab scholar and collector of manuscripts, Girqis Safa,3 from a manuscript he owned, dated to the year 1389. After the death of Safa the manuscript disappeared and after a few decades it re-emerged in Egypt, in the Ahmad Taymur4 collection of the National Library of Cairo, where it remains to this day (Codex Ahmad Taymur 103). This Arabic manuscript was also published in Frankfurt in 1987 by Professor Dr. Fuat Sezgin.5

The English translation that follows is based on the French translation by Girgis Safa. The translation has been verified by Dr. Gamal al-Tahir, so it is rendered as accurately as possible.

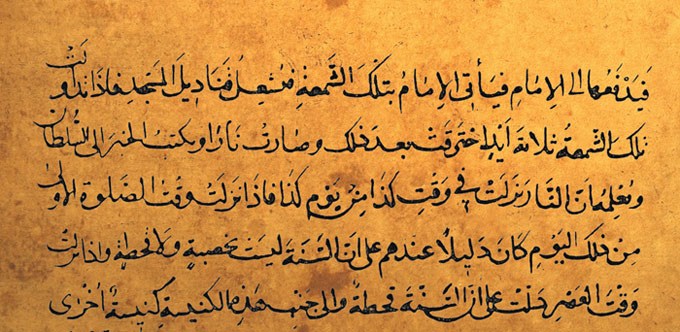

The reference by Ibn al-Qass to the Holy Fire in the valuable manuscript Ahmad Taymur 103 (c. 1389) of the National Library of Egypt. The narrative begins at the end of folio 47 and continues on folio 48.

In his work Ibn al-Qass writes:

|

فإذا كان فصح النصارى وهو يوم السبت الكبير وذلك يوم يخرج الناس من موضع القبر إلى الصخرة وحول الصخرة داربزينات يتطلعون إلى موضع القبر يبتهلون كلهم ويتضرعون إلى الله تعالى من وقت الأولى إلى المغرب ويحضر الأمير وإمام المسجد. ويغلق السلطان الباب الذي على القبر ويقعد على الباب فهم على هذا حتى يرون نورا كأنه نار بيضاء تخرج من جوف القبر. فيفتح السلطان الباب عن القبر ويدخل إليها وفي يده شمعة فيشعلها من ذلك النور فيخرجها والشمعة تشتعل و. فيدفعها إلى الإمام فيأتي الإمام بتلك الشمعة فيشعل قناديل المسجد. فإذا تداولت تلك الشمعة ثلاثة أيد احترقت بعد ذلك وصارت نارا. ويكتب الخبر إلى السلطان ويعلمه ان النار نزلت في وقت كذا من يوم كذا. فإذا نزلت وقت الصلوات الأولى من ذلك اليوم كانت دليلا عندهم على أن السنة ليست بخصبة ولا قحطة وإذا نزلت وقت العصر .دلت على أن السنة قحطة

|

On the Easter of the Christians, on Holy Saturday, the faithful exit from the place of the tomb in order to gather around the rock that is surrounded by railing. From there they look upon the tomb and all together they pray and kneel before the Almighty God, from the morning prayer until the setting of the sun. The emir and the imam of the mosque are also present. The sultan locks the door to the tomb. They all remain still until they see a light similar to a white flame which comes from the interior of the tomb. The sultan then opens the door and enters holding a candle, which he lights with this flame and then emerges. The flame of this lit candle does not burn. He gives it to the imam who transfers it and lights the lamps of the mosque. Once this candle has passed to three hands, then it burns and is transformed into a (regular) flame. Then they compose and deliver to the sultan a report verifying that the flame had come on such an hour and day. If it has appeared on that day during the hour of prayer it is for them a sign that the year will not be fertile, without this meaning that it will be a year of drought. If the flame has appeared at the noon hour, this indicates a year with lack of food.6 |

The report by Ibn al-Qass is very significant because it comes from a particularly devout scholar of Muslim law. As he records, the Muslim leaders of Jerusalem have absolute control of the rite. Present are the imam of the mosque, the emir and the sultan (السلطان), who is the only one who holds the keys to the Tomb.

During the ceremony the faithful pray and the Orthodox patriarch embarks on the traditional invocation for the descent of the Holy Fire while remaining outside the Tomb, before the entire mass of people.

Everything takes place in the open. The Sepulchre is locked and empty. And suddenly a white light emerges from the interior of the Tomb. It is the supernatural light that comes from the actual Tomb itself. Then the sultan unlocks the Tomb and enters to light his candle, and when he emerges he delivers it to the imam. The Muslims participate to such an extent and in such an official capacity, that one would think that the rite is theirs.

Of extreme significance is also the testimony that the holy flame does not burn. Ibn al-Qass fully distinguishes the light that appears in the Tomb interior from the flame that is received by the faithful a few moments later on their candles. His report is exceptionally precise. He uses the word نور which means light and the word نار which means fire.

When the Holy Light appears it is deemed by the Muslims to be a divine white light that is not at all related to earthly fire. When, however, this divine flame spreads from candle to candle, after “three hands” as he states, in other words within a few seconds, the heavenly light becomes earthly. It is transformed from نور to نار, in other words from divine light to earthly fire.

When the sultan exits with the lit candle from the interior of the Holy Sepulchre, the flame of his candle does not burn. Ibn al-Qass uses the phrase لا تحترق which means “is not burned” or “does not burn.” In the French translation by Safa we find “ne se consume pas,” but this does not render the meaning with clarity. According to Gamal al-Tahir there is no doubt that the meaning of the phrase is “the flame of the candle does not burn.” This is the familiar phenomenon that the Holy Fire does not burn, which is still observed to this day.

The moment the ever-burning lamp ignites inside the Sepulchre, the light has a bluish white colour and does not burn at all. A few seconds later it is transformed into a flame which, as ascertained by the author and thousands of faithful, obviously burns but not with the same intensity as a regular flame.

Pilgrims “bathe” their faces with the Holy Fire. Over a thousand years ago,

Ibn al-Qass was the first to record that the Holy Fire does not burn.

The acceptance of the miracle by the Muslim community of Jerusalem becomes even more apparent from the statement that with the Holy Fire the imam (the leader of the mosque) lights “the lamps inside the mosque,” meaning the Dome of the Rock, which is considered to be the third most sacred mosque in the Muslim world after Mecca and Medina. The Holy Fire is spread by the imam to the most sacred area of the Muslims of Jerusalem.

The Dome of the Rock, completed in 691. Under the dome is a rock from which Muslims believe their prophet, Mohammed, ascended to the heavens. In the mid-tenth century the Muslim imam lit the lamps of this shrine with a flame from the Holy Fire, every Holy Saturday.

All this took place in the first half of the tenth century, at a time when the Christian and Muslim worlds were in great conflict. Considering the austerity of the Muslim religion, it seems unbelievable that the most significant miracle of the Christian world, which is associated with the Resurrection of Jesus Christ, was accepted by the Muslims of Jerusalem and celebrated with the official participation of the city’s political and religious leaders.

The narrative of Ibn al-Qass conveys a very bright message that reveals much about the authenticity of the miracle, but also about the very Resurrection of Jesus Christ.

Notes:

1. His full name is Abi Ahmad al-Tabari Ibn al-Qass.

2. MS Ahmad Taymur 103 & MS Miqat 1201. Cairo, National Library; MS Veliyuddin 2453. Istanbul, Beyazit Library; MS XXXIV. Madrid, Collection Gayangos; Ms Oriental 13315, AD 1705. London, British Library. It is the only manuscript that contains the entire work (fols. 2v–57r). Three of the five manuscripts are analyzed by J.-C. Ducène in her work “Le Kitab dala’il al-qibla d’Ibn al-Qass: analyse de trois manuscrits et des emprunts d’Abu Hamid al-Garnati,” ZGAIW 14 (2001), pp. 169–87.

3. Q. Safa, “Les Manuscrits de ma Bibliotheque,” Al-Masriq 16, Beirut 1913.

4. The collection of Ahmad Taymur (1877–1930) numbers 15,415 books and manuscripts, and is the second largest private collection in Egypt.

5. F. Sezgin, “Kitab dala’il al-qibla li-ibn al-Qass”, Das Buch über die Orientierung nach Mekka von Ibn al-Qass, ZGAIW 4 (1987–88), pp. 7–92. Prof. Dr. Fuat Sezgin is director of the Institute for the History of Arabic-Islamic Science at the Johann W. Goethe University of Frankfurt.

6. The French translation of the original Arabic is as follows: “La Pâques des Chrétiens, le Samedi Saint, les gens sortent de l’emplacement du tombeau pour aller au rocher autour duquel sont les balustrades; (de là) ils regardent le tombeau, tous prient, se prosternent devant Dieu le Très-Haut, depuis la première prière du matin jusqu’au coucher du soleil. L’émir et l’imâm de la mosquée y sont présents. Le gouverneur verrouille la porte de sépulcre. Ils restent tous ainsi [sans bouger], tant qu’ils ne voient pas une lumière semblable à un feu blanc sortant de l’intérieur du tombeau. Le gouverneur ouvre alors la porte du sépulcre et y entre tenant un cierge qu’il allume à ce feu, et ensuite il le sort. Le cierge allumé ne se consume pas. Il le passe à l’imâm qui l’emporte et en allumé les lampes de la mosquée. Quand ce cierge est passé en trois mains, il se consume et se transforme en feu. Puis on rédige et on remet au gouverneur un rapport constatant que le feu est descendu telle heure et tel jour. S’il est descendu ce jour-là à l’heure de la prière, c’est pour eux un signe que l’année ne sera pas fertile, sans que ce soit une année de sécheresse; s’il est descendu à l’heure de midi, cela indique une année de disette” (G. Safa, in Al-Machriq 16, 1913, pp. 578–79). For a Russian translation, see I.J. Krachkovsky, “Blagodatny ogon’’, Christiansky Vostok 3 (1915), pp. 232–33.